A portfolio of six iPhone selfies of my fingers, called "In Our Hands," and my written responses to six standard interview questions (Who? What? When? Where? Why? How?), were published in the Fall 2014 issue (pages 32-41) of Short, Fast, & Deadly, an online journal of flash fiction and imagery (see http://issuu.com/deadlychaps/docs/2014.3fallissuu/33?e=3372778/10722493).

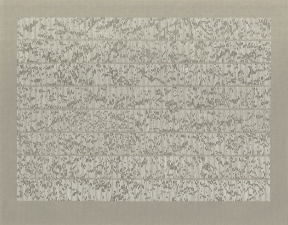

In Laid Line drawings, I draw on the creases that the wire papermaking mold leaves imprinted on the paper, during the paper's production process. These creases form the understructure of any drawing or document created on laid paper. When my lines are broken, they also map the thickness of the paper: dark lines note where the pulp is thickest, and white lines show where light shines through.

Larger Laid Line drawings take days to complete, and the intensity of the ink is affected by atmospheric conditions in the studio and its surrounding weather patterns. This was especially the case during a 2007 residency at the Edward F. Albee Foundation, where the studio was part of an old barn.

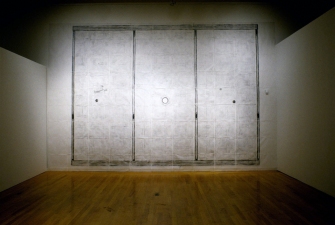

Rubbings (60 x 60 inches each) of the floorboards underneath each of the seven Agnes Martin paintings permanently installed at the Harwood Museum of Art in Taos, New Mexico. One set of rubbings is all in graphite, using two side-by-side pieces of rice paper; another set uses different sizes of rice paper as well as combinations of graphite and colored pencils.

The floorboards of this octagonal space are all laid side by side, so a rubbing yields a field of parallel lines that echoes the bands of Martin's paintings. The direction of my lines, however, is not consistently horizontal: only one painting hangs so that its lines mirror those of the floorboards beneath. I see my drawings as literal and figurative "twists" on Martin's paintings: shifting the lines' directions and shifting the viewer's perspective (again, literally and figurative) on her paintings. When I revisit her work from the floor, I think about the underbelly of her (or any) artistic endeavor, and Martin's titles open to new interpretations. (I only learned in 2014 that Martin often used the neologism "un-love" in conversation.) The drawings show pieces of hair, rips where small stones tore the thin rice paper, and many scratches in the floorboards from years of use.

The floorboards of this octagonal space are all laid side by side, so a rubbing yields a field of parallel lines that echoes the bands of Martin's paintings. The direction of my lines, however, is not consistently horizontal: only one painting hangs so that its lines mirror those of the floorboards beneath. I see my drawings as literal and figurative "twists" on Martin's paintings: shifting the lines' directions and shifting the viewer's perspective (again, literally and figurative) on her paintings. When I revisit her work from the floor, I think about the underbelly of her (or any) artistic endeavor, and Martin's titles open to new interpretations. (I only learned in 2014 that Martin often used the neologism "un-love" in conversation.) The drawings show pieces of hair, rips where small stones tore the thin rice paper, and many scratches in the floorboards from years of use.

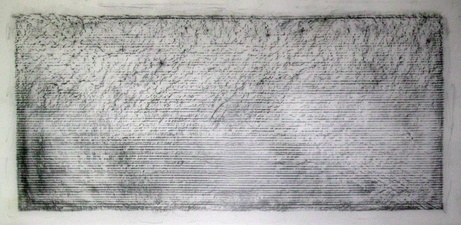

Rubbings of the mat Agnes Martin used to stand on in while painting in her studio in Taos, New Mexico.

In 2007, this mat was being used for construction workers to wipe their feet as they passed through the doorway of Agnes Martin's studio in Taos, New Mexico. The site was being transformed into a children's toy store. Because I had visited the studio in 2006, when the property was for sale but empty and untouched, I recognized the rubber mat by its (uncanny) parallel lines and its paint drips. When I told a site supervisor about the mat's origin, she was surprised and asked me if I wanted it.

By standing where Martin stood to make her paintings, I had the strange sense that I physically "under-stood" something about their surfaces: how they simultaneously invite and refuse access. (The rubber mat both buoys you up and cushions your weight.) The parallel lines of my drawing, unlike Martin's geometries, reveal "dirt" and messiness. We create art from whatever mess we can access; as we proceed, we leave dirt behind. These drawings feel to me like emblems of the unconscious foundation beneath any endeavor, a layer that Martin, especially, sought carefully to contain.

In 2007, this mat was being used for construction workers to wipe their feet as they passed through the doorway of Agnes Martin's studio in Taos, New Mexico. The site was being transformed into a children's toy store. Because I had visited the studio in 2006, when the property was for sale but empty and untouched, I recognized the rubber mat by its (uncanny) parallel lines and its paint drips. When I told a site supervisor about the mat's origin, she was surprised and asked me if I wanted it.

By standing where Martin stood to make her paintings, I had the strange sense that I physically "under-stood" something about their surfaces: how they simultaneously invite and refuse access. (The rubber mat both buoys you up and cushions your weight.) The parallel lines of my drawing, unlike Martin's geometries, reveal "dirt" and messiness. We create art from whatever mess we can access; as we proceed, we leave dirt behind. These drawings feel to me like emblems of the unconscious foundation beneath any endeavor, a layer that Martin, especially, sought carefully to contain.

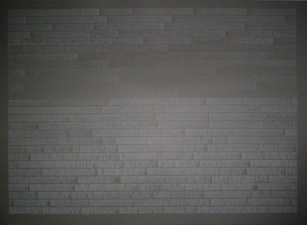

Rubbings of the floor and ceiling of the exhibition space, mounted on opposite walls as if the room had been rotated. The history recorded in surface details was revealed, and the "white cube" could be seen from fresh perspectives. This was my M.F.A thesis exhibition -- my colleagues and I were asking where we would go "from here." Also, we endured controversies about whether M.F.A. thesis shows would have to move "from here" to an off-campus venue. Mostly, however, I was concerned with the act of looking (at art), and what visitors might see if they could look ("from here") at the place on/under which they were standing.